Medical information

From the list below select the procedures you are interested in and find useful information about them.

Knee

Total Knee ReplacementUnicompartmental Arthroplasty and Tibial Osteotomy

Arthroscopic Meniscectomy

ACL reconstruction / PCL reconstruction

Hip

Minimally Invasive Total Hip ReplacementBack

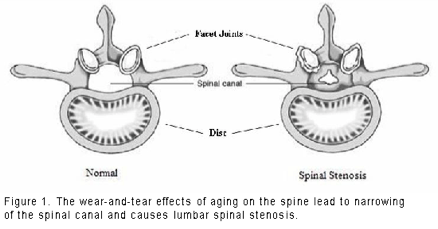

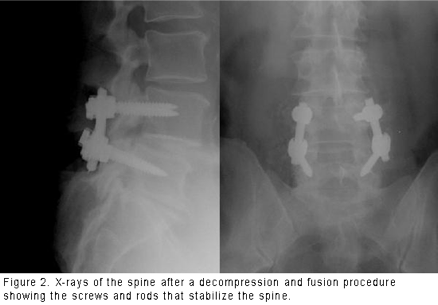

Herniated Disc SurgeryLumbar Spinal Stenosis. Laminectomy

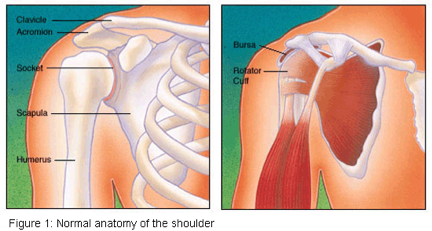

Shoulder

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff RepairArthroscopic Shoulder Decompression

Hand

Carpal tunnel releaseFasciectomy for Dupuytren’s Contracture

Carpal tunnel release

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Introduction

Some people might think that carpal tunnel syndrome is a new condition of the information technology age, born from long hours of computer keyboarding. But carpal tunnel syndrome isn't new. Evidence of people experiencing signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome occurs in medical records dating back to the beginning of the 20th century.

Bounded by bones and ligaments, the carpal tunnel is a narrow passageway — about as big around as your thumb — located on the palm side of your wrist. This tunnel protects a main nerve to your hand and nine tendons that bend your fingers. Pressure placed on the nerve produces the numbness, pain and, eventually, hand weakness that characterize carpal tunnel syndrome.

Fortunately, for most people who develop carpal tunnel syndrome, proper treatment usually can relieve the pain and numbness and restore normal use of the wrists and hands.

Signs and symptoms

Carpal tunnel syndrome typically starts gradually with a vague aching in your wrist that can extend to your hand or forearm. Other common carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms include:

• Tingling or numbness in your fingers or hand, especially your thumb, index, middle or ring fingers, but not your little finger. This sensation often occurs while driving a vehicle or holding a phone or a newspaper or upon awakening. Many people "shake out" their hands to relieve their symptoms.

• Pain radiating or extending from your wrist up your arm to your shoulder or down into your palm or fingers, especially after forceful or repetitive use. This usually occurs on palm side of your forearm.

• A sense of weakness in your hands and a tendency to drop objects.

• A constant loss of feeling in some fingers. This can occur if the condition is advanced.

Causes

The cause of carpal tunnel syndrome is pressure on the median nerve. The median nerve is a mixed nerve, meaning it has a sensory function and also provides nerve signals to move your muscles (motor function). The median nerve provides sensation to your thumb, index finger, middle finger and the middle-finger side of the ring finger.

Pressure on the nerve can stem from anything that reduces the space for it in the carpal tunnel. Causes might include anything from bone spurs to the most common cause, which is swelling or thickening of the lining and lubricating layer (synovium) of the tendons in your carpal tunnel.

The exact cause of the swelling usually isn't known, but a variety of conditions and factors can play a role:

• Other health conditions. Some examples include rheumatoid arthritis, certain hormonal disorders — such as diabetes, thyroid disorders and menopause — fluid retention due to pregnancy, or deposits of amyloid, an abnormal protein produced by cells in your bone marrow.

• Repetitive use or injury. Repetitive flexing and extending of the tendons in the hands and wrists, particularly when done forcefully and for prolonged periods without rest, also can increase pressure within the carpal tunnel. Injury to your wrist can cause swelling that exerts pressure on the median nerve.

• Physical characteristics. It may be that your carpal tunnel is more narrow than average. Other less common causes include a generalized nerve problem or pressure on the median nerve at more than one location.

Risk factors

Some studies suggest that carpal tunnel syndrome can result from overuse or strain in certain job tasks that require a combination of repetitive, forceful and awkward or stressed motions of your hands and wrists. Examples of these include using power tools — such as chippers, grinders, chain saws or jackhammers — and heavy assembly line work, such as occurs in a meatpacking plant. Although repetitive computer use is commonly assumed to cause carpal tunnel syndrome, the scientific evidence for this association isn't definitive.

Although it's not clear which activities can cause carpal tunnel syndrome, if your work or hobbies are hand-intensive — involving a combination of awkward, repetitive wrist or finger motions, forceful pinching or gripping, and working with vibrating tools — you may be at higher risk of developing the condition.

Other risk factors include:

• Your sex. Women are three times as likely as men are to develop carpal tunnel syndrome. The incidence in women peaks after menopause, and the risk of carpal tunnel syndrome also increases in men during middle age.

• Heredity. You may be significantly more likely to develop carpal tunnel syndrome if close relatives have had the condition. Inherited physical characteristics, such as the shape of your wrist, may make you more susceptible.

• Certain health conditions. Conditions including some thyroid problems, diabetes, obesity and rheumatoid arthritis can increase your risk. Women who are pregnant, taking oral contraceptives or going through menopause also are at increased risk, most likely due to hormonal changes. Fluid retention may be a cause of carpal tunnel syndrome during pregnancy. Fortunately, carpal tunnel syndrome related to pregnancy almost always improves after childbirth. People who smoke cigarettes may experience worse symptoms and slower recovery from carpal tunnel syndrome than nonsmokers do.

When to seek medical advice

If signs and symptoms that you think might be due to carpal tunnel syndrome interfere with your normal activities — including sleep — and if they persist, see your doctor. If you leave the condition untreated, nerve and muscle damage can occur.

Screening and diagnosis

Your doctor will most likely want to review your signs and symptoms to find out where they're located. One diagnostic key is that the median nerve doesn't provide sensation to the little finger, so symptoms in that finger may indicate a different problem. Another clue is the timing of the symptoms. Typical times when you might experience symptoms due to carpal tunnel syndrome include while holding a phone or a newspaper, gripping a steering wheel, or waking up during the night.

Your doctor will also want to test the feeling in your fingers and the strength of the muscles in your hand, because these can be affected by carpal tunnel syndrome. Pressure on the median nerve at the wrist, produced by either bending the wrist, tapping on the nerve or simply pressing on the nerve, can bring on the symptoms in many people.

If you have signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome, your doctor may recommend the following diagnostic tests:

• Electromyogram. Electromyography measures the tiny electrical discharges produced in muscles. A thin-needle electrode is inserted into the muscles your doctor wants to study. An instrument records the electrical activity in your muscle at rest and as you contract the muscle. This test can help determine if muscle damage has occurred.

• Nerve conduction study. In a variation of electromyography, two electrodes are taped to your skin. A small shock is passed through the median nerve to see if electrical impulses are slowed in the carpal tunnel.

These tests are also useful in checking for other conditions that might mimic carpal tunnel syndrome, such as a pinched nerve in your neck. Your doctor may recommend that you see a rheumatologist, neurologist, hand surgeon or neurosurgeon if your signs or symptoms indicate other medical disorders or a need for specialized treatment.

Treatment

Some people with mild symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome can ease their discomfort by taking more frequent breaks to rest their hands and applying cold packs to reduce occasional swelling. If these techniques don't offer relief, carpal tunnel syndrome treatment options include wrist splinting, medications and surgery.

Nonsurgical therapy

Most people with carpal tunnel syndrome experience effective treatment with nonsurgical methods, including:

• Wrist splinting. A splint that holds your wrist still while you sleep can help relieve nighttime symptoms of tingling and numbness. Splinting is more likely to help you if you've had only mild to moderate symptoms for less than a year.

• Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs may help relieve pain from carpal tunnel syndrome if you have an associated inflammatory condition. If no inflammatory condition is involved, NSAIDs are unlikely to help relieve your symptoms.

• Corticosteroids. Your doctor may inject your carpal tunnel with a corticosteroid, such as cortisone, to relieve your pain. Corticosteroids decrease inflammation, thus relieving pressure on the median nerve. Oral corticosteroids aren't as effective as corticosteroid injections for treating carpal tunnel syndrome.

Surgery

Generally, nonsurgical treatments are more effective if you have only mild nerve impairment. When the pain or numbness of carpal tunnel syndrome persists, surgery may be the best option.

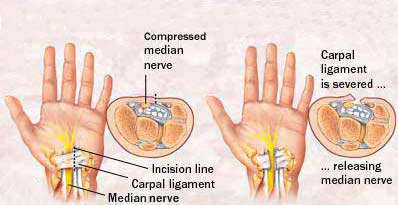

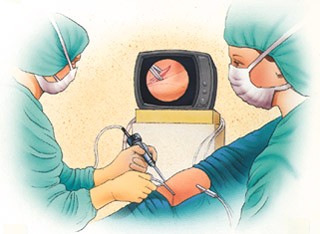

Your surgeon may use one of a few accepted techniques. But in all accepted surgical procedures, your doctor cuts the ligament pressing on your nerve. At times, surgery can be done using an endoscope, a telescope-like device with a tiny camera attached to it that allows your doctor to see inside your carpal tunnel and perform the surgery through small incisions in your hand or wrist. In other cases, surgery involves making an incision in the palm of your hand over the carpal tunnel and releasing the nerve.

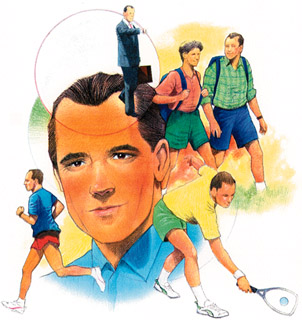

Surgery usually results in marked improvement, but you may experience some residual numbness, pain, stiffness or weakness. Surveys of people who have undergone carpal tunnel release indicate that about 70 percent are completely or very satisfied with the outcome of their surgery. Some variables that are associated with lower levels of satisfaction include consuming more than two alcoholic drinks a day, smoking, lower mental and physical health status before surgery, and exposure to repetitive, forceful activity — but not including keyboard use.

After surgery, your doctor may tell you that limited use of your hand and wrist is OK within a few days. However, it may take from several weeks to as long as a few months before you have unrestricted use of your hand and wrist. If surgery appears to be the best alternative for relieving your symptoms or preventing further muscle atrophy, be sure to talk with your surgeon about the procedure that will work best for you and with your plans to return to your previous activity levels, both at work and at home.

If carpal tunnel syndrome results from an inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, then treating the underlying condition generally also reduces the carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms.

Carpal tunnel release

During carpal tunnel release, the transverse carpal tunnel ligament is severed to relieve pressure on the median nerve. The surgery may be done by making one incision on the palm side of the wrist, ...

Prevention

There are no proven strategies to prevent carpal tunnel syndrome, but to protect your hands from a variety of ailments, take the following precautions:

• Reduce your force and relax your grip. Most people use more force than needed to perform many tasks involving the hands. If your work involves a cash register, for instance, hit the keys softly. For prolonged handwriting, use a big pen with an oversized, soft grip adapter and free-flowing ink. This way you won't have to grip the pen tightly or press as hard on the paper.

• Take frequent breaks. Every 15 to 20 minutes give your hands and wrists a break by gently stretching and bending them. Alternate tasks when possible. If you use equipment that vibrates or that requires you to exert a great amount of force, taking breaks is even more important.

• Watch your form. Avoid bending your wrist all the way up or down. A relaxed middle position is best. If you use a keyboard, keep it at elbow height or slightly lower.

• Improve your posture. Incorrect posture can cause your shoulders to roll forward. When your shoulders are in this position, your neck and shoulder muscles are shortened, compressing nerves in your neck. This can affect your wrists, fingers and hands.

• Keep your hands warm. You're more likely to develop hand pain and stiffness if you work in a cold environment. If you can't control the temperature at work, put on fingerless gloves that keep your hands and wrists warm.

Self-care

Quick breaks, stretching, aspirin or other over-the-counter NSAIDs may relieve your symptoms temporarily.

You might also want to try wearing a wrist splint at night and avoid sleeping on your hands to help ease the pain or numbness in your wrists and hands. The splint should be snug but not tight. If pain, numbness or weakness recurs and persists, see your doctor.

Coping skills

If you experience chronic pain or can't use your hands as before, you may become depressed or experience low self-esteem. In addition, if your hand symptoms are caused or worsened by your current profession or leisure activities, you may face the tough decision of switching careers or giving up hobbies. You may also feel that you aren't actively contributing to your family if you can't drive a car or perform ordinary household tasks.

Support groups for people with carpal tunnel syndrome can help you find out more information about your condition plus offer advice and solace. Stress management and relaxation techniques also may help you deal with the psychological and emotional issues that may accompany carpal tunnel syndrome.

Complementary and alternative medicine

Yoga and other relaxation techniques may help with chronic pain that occurs with some muscle and joint conditions. Yoga postures designed for strengthening, stretching and balancing each joint in the upper body, as well as the upper body itself, may help reduce the pain and improve the grip strength of people with carpal tunnel syndrome.

Other options for treatment involve special types of physical therapy. Many of the methods used for c

arpal tunnel syndrome include:

• Heat

• Massage

• Water therapy (hydrotherapy)

You may have to experiment to find a treatment that works for you. Still, always check with your doctor before trying any complementary or alternative treatment.

Total Knee Replacement

Total Knee Replacement

General information

If your knee is severely damaged by arthritis or injury, it may be hard for you to perform simple activities such as walking or climbing stairs. You may even begin to feel pain while you're sitting or lying down.

If medications, changing your activity level and using walking supports are no longr helpful, you may want to consider total knee replacement surgery. By resurfacing your knee's damaged and worn surfaces, total knee replacement surgery can relieve your pain, correct your leg deformity and help you resume your normal activities.

One of the most important orthopaedic surgical advances of the twentieth century, knee replacement was first performed in 1968. Improvements in surgical materials and techniques since then have greatly increased its effectiveness. Approximately 300,000 knee replacements are performed each year in the United States.

Whether you have just begun exploring treatment options or have already decided with your orthopaedic surgeon to have total knee replacement surgery, this booklet will help you understand more about this valuable procedure.

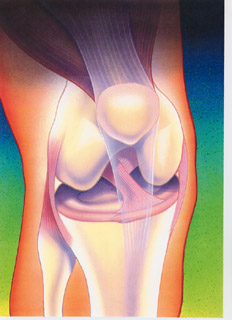

How the Normal Knee Works

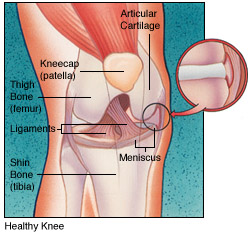

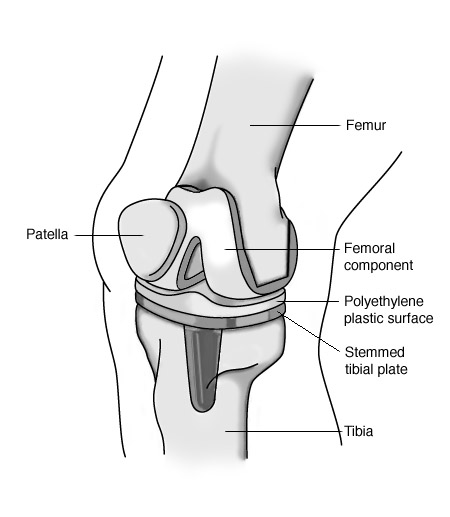

The knee is the largest joint in the body. Nearly normal knee function is needed to perform routine everyday activities. The knee is made up of the lower end of the thigh bone (femur), which rotates on the upper end of the shin bone (tibia), and the knee cap (patella), which slides in a groove on the end of the femur. Large ligaments attach to the femur and tibia to provide stability. The long thigh muscles give the knee strength.

The joint surfaces where these three bones touch are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth substance that cushions the bones and enables them to move easily.

All remaining surfaces of the knee are covered by a thin, smooth tissue liner called the synovial membrane. This membrane releases a special fluid that lubricates the knee, reducing friction to nearly zero in a healthy knee.

Normally, all of these components work in harmony. But disease or injury can disrupt this harmony, resulting in pain, muscle weakness and less function.

Common Causes of Knee Pain and Loss of Knee Function

The most common cause of chronic knee pain and disability is arthritis. Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and traumatic arthritis are the most common forms.

Osteoarthritis usually occurs after the age of 50 and often in an individual with a family history of arthritis. The cartilage that cushions the bones of the knee softens and wears away. The bones then rub against one another, causing knee pain and stiffness.

Rheumatoid Arthritis is a disease in which the synovial membrane becomes thickened and inflamed, producing too much synovial fluid that over-fills the joint space. This chronic inflammation can damage the cartilage and eventually cause cartilage loss, pain and stiffness.

Traumatic Arthritis can follow a serious knee injury. A knee fracture or severe tears of the knee's ligaments may damage the articular cartilage over time, causing knee pain and limiting knee function.

Is Total Knee Replacement for You?

The decision whether to have total knee replacement surgery should be a cooperative one between you, your family, your family physician and your orthopaedic surgeon. Your physician may refer you to an orthopaedic surgeon for a thorough evaluation to determine if you could benefit from this surgery. Alternatives to traditional total knee replacement surgery that your orthopaedic surgeon may discuss with you include a unicompartmental knee replacement or a minimally invasive knee replacement.

Reasons that you may benefit from total knee replacement commonly include:

• Severe knee pain that limits your everyday activities, including walking, going up and down stairs, and getting in and out of chairs. You may find it hard to walk more than a few blocks without significant pain and you may need to use a cane or walker.

• Moderate or severe knee pain while resting, either day or night

• Chronic knee inflammation and swelling that doesn't improve with rest or medications

• Knee deformity--a bowing in or out of your knee

• Knee stiffness--inability to bend and straighten your knee

• Failure to obtain pain relief from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These medications, including aspirin and ibuprofen, often are most effective in the early stages of arthritis. Their effectiveness in controlling knee pain varies greatly from person to person. These drugs may become less effective for patients with severe arthritis.

• Inability to tolerate or complications from pain medications

• Failure to substantially improve with other treatments such as cortisone injections, physical therapy, or other surgeries

Most patients who undergo total knee replacement are age 60 to 80, but orthopaedic surgeons evaluate patients individually. Recommendations for surgery are based on a patient's pain and disability, not age. Total knee replacements have been performed successfully at all ages, from the young teenager with juvenile arthritis to the elderly patient with degenerative arthritis.

The Orthopaedic Evaluation

The orthopaedic evaluation consists of several components:

• A medical history, in which your orthopaedic surgeon gathers information about your general health and asks you about the extent of your knee pain and your ability to function

• A physical examination to assess your knee motion, stability, strength and overall leg alignment

• X-rays to determine the extent of damage and deformity in your knee

• Occasionally blood tests, a Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI) or a bone scan may be needed to determine the condition of the bone and soft tissues of your knee.

•

Your orthopaedic surgeon will review the results of your evaluation with you and discuss whether total knee replacement would be the best method to relieve your pain and improve your function. Other treatment options--including medications, injections, physical therapy, or other types of surgery--also will be discussed and considered.

Your orthopaedic surgeon also will explain the potential risks and complications of total knee replacement, including those related to the surgery itself and those that can occur over time after your surgery.

Realistic Expectations About Knee Replacement Surgery

An important factor in deciding whether to have total knee replacement surgery is understanding what the procedure can and can't do.

More than 90 percent of individuals who undergo total knee replacement experience a dramatic reduction of knee pain and a significant improvement in the ability to perform common activities of daily living. But total knee replacement won't make you a super-athlete or allow you to do more than you could before you developed arthritis.

Following surgery, you will be advised to avoid some types of activity, including jogging and high impact sports, for the rest of your life.

With normal use and activity, every knee replacement develops some wear in its plastic cushion. Excessive activity or weight may accelerate this normal wear and cause the knee replacement to loosen and become painful. With appropriate activity modification, knee replacements can last for many years.

Preparing for Surgery

Medical Evaluation

If you decide to have total knee replacement surgery, you may be asked to have a complete physical by your family physician several weeks before surgery to assess your health and to rule out any conditions that could interfere with your surgery.

Tests

Several tests-such as blood samples, a cardiogram and a urine sample-may be needed to help your orthopaedic surgeon plan your surgery.

Preparing Your Skin and Leg

Your knee and leg should not have any skin infections or irritation. Your lower leg should not have any chronic swelling. Contact your orthopaedic surgeon prior to surgery if either of these conditions is present for a program to best prepare your skin for surgery.

Blood Donation

You may be advised to donate your own blood prior to the surgery. It will be stored in the event you need blood after your surgery.

Medications

Tell your orthopaedic surgeon about the medications you are taking. He or she will tell you which medications you should stop taking and which you should continue to take before surgery.

Dental Evaluation

Although the incidence of infection after knee replacement is very low, an infection can occur if bacteria enter your bloodstream. Treatment of significant dental diseases (including tooth extractions and periodontal work) should be considered before your total knee replacement surgery.

Urinary Evaluations

A preoperative urological evaluation should be considered for individuals with a history of recent or frequent urinary infections. For older men with prostate disease, required treatment should be considered prior to knee replacement surgery.

Social Planning

Though you will be able to walk on crutches or a walker soon after surgery, you will need help for several weeks with such tasks as cooking, shopping, bathing and doing laundry. If you live alone, your surgeon's office and a social worker or a discharge planner at the hospital can help you make advance arrangements to have someone assist you at home. They also can help you arrange for a short stay in an extended care facility during your recovery, if this option works best for you.

Home Planning

Several suggestions can make your home easier to navigate during your recovery. Consider:

• Safety bars or a secure handrail in your shower or bath

• Secure handrails along your stairways

• A stable chair for your early recovery with a firm seat cushion (height of 18-20 inches), a firm back, two arms, and a footstool for intermittent leg elevation

• A toilet seat riser with arms, if you have a low toilet

• A stable shower bench or chair for bathing

• Removing all loose carpets and cords

• A temporary living space on the same floor, because walking up or down stairs will be more difficult during your early recovery

Your Surgery

You will most likely be admitted to the hospital on the day of your surgery. After admission, you will be evaluated by a member of the anesthesia team. The most common types of anesthesia are general anesthesia, in which you are asleep throughout the procedure, and spinal or epidural anesthesia, in which you are awake but your legs are anesthetized. The anesthesia team will determine which type of anesthesia will be best for you with your input.

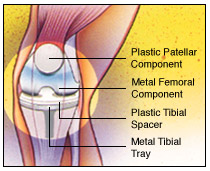

The procedure itself takes about two hours. Your orthopaedic surgeon will remove the damaged cartilage and bone and then position the new metal and plastic joint surfaces to restore the alignment and function of your knee.

Many different types of designs and materials are currently used in total knee replacement surgery. Nearly all of them consist of three components: the femoral component (made of a highly polished strong metal), the tibial component (made of a durable plastic often held in a metal tray), and the patellar component (also plastic).

After surgery, you will be moved to the recovery room, where you will remain for one to two hours while your recovery from anesthesia is monitored. After you awaken, you will be taken to your hospital room.

Your Stay in the Hospital

You will most likely stay in the hospital for several days. After surgery, you will feel some pain, but medication will be given to you to make you feel as comfortable as possible. Pain management is an important part of your recovery, so talk with your surgeon if postoperative pain becomes a problem. Walking and knee movement are important to your recovery and will begin immediately after your surgery.

To avoid lung congestion after surgery, you should breathe deeply and cough frequently to clear your lungs.

Your orthopaedic surgeon may prescribe one or more measures to prevent blood clots and decrease leg swelling, such as special support hose, inflatable leg coverings (compression boots) and blood thinners.

To restore movement in your knee and leg, your surgeon may use a knee support that slowly moves your knee while you are in bed. The device, called a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine, decreases leg swelling by elevating your leg and improves your venous circulation by moving the muscles of your leg.

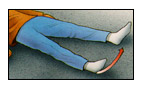

Foot and ankle movement also is encouraged immediately following surgery to increase blood flow in your leg muscles to help prevent leg swelling and blood clots. Most patients begin exercising their knee the day after surgery. A physical therapist will teach you specific exercises to strengthen your leg and restore knee movement to allow walking and other normal daily activities soon after your surgery.

Possible Complications After Surgery

The complication rate following total knee replacement is low. Serious complications, such as a knee joint infection, occur in less than 2 percent of patients. Major medical complications such as heart attack or stroke occur even less frequently. Chronic illnesses may increase the potential for complications. Although uncommon, when these complications occur, they can prolong or limit your full recovery.

Blood clots in the leg veins are the most common complication of knee replacement surgery. Your orthopaedic surgeon will outline a prevention program, which may include periodic elevation of your legs, lower leg exercises to increase circulation, support stockings and medication to thin your blood.

Although implant designs and materials as well as surgical techniques have been optimized, wear of the bearing surfaces or loosening of the components may occur. Additionally, although an average of 115 degrees of motion is generally anticipated after surgery, scarring of the knee can occasionally occur and motion may be more limited. This is particularly true in patients with limited motion before surgery. Finally, while rare, injury to the nerves or blood vessels around the knee can occur during surgery.

Discuss your concerns thoroughly with your orthopaedic surgeon prior to surgery.

Your Recovery at Home

The success of your surgery also will depend on how well you follow your orthopaedic surgeon's instructions at home during the first few weeks after surgery.

Wound Care

You will have stitches or staples running along your wound or a suture beneath your skin on the front of your knee. The stitches or staples will be removed several weeks after surgery. A suture beneath your skin will not require removal.

Avoid soaking the wound in water until the wound has thoroughly sealed and dried. The wound may be bandaged to prevent irritation from clothing or support stockings.

Diet

Some loss of appetite is common for several weeks after surgery. A balanced diet, often with an iron supplement, is important to promote proper tissue healing and restore muscle strength.

Activity

Exercise is a critical component of home care, particularly during the first few weeks after surgery. You should be able to resume most normal activities of daily living within three to six weeks following surgery. Some pain with activity and at night is common for several weeks after surgery. Your activity program should include:

• A graduated walking program to slowly increase your mobility, initially in your home and later outside

• Resuming other normal household activities, such as sitting and standing and walking up and down stairs

• Specific exercises several times a day to restore movement and strengthen your knee. You probably will be able to perform the exercises without help, but you may have a physical therapist help you at home or in a therapy center the first few weeks after surgery.

Driving usually begins when your knee bends sufficiently so you can enter and sit comfortably in your car and when your muscle control provides adequate reaction time for braking and acceleration. Most individuals resume driving about four to six weeks after surgery.

Avoiding Problems After Surgery

Blood Clot Prevention

Follow your orthopaedic surgeon's instructions carefully to minimize the potential of blood clots that can occur during the first several weeks of your recovery.

Warning signs of possible blood clots in your leg include:

• Increasing pain in your calf

• Tenderness or redness above or below your knee

• Increasing swelling in your calf, ankle and foot

Warning signs that a blood clot has traveled to your lung include:

• Sudden increased shortness of breath

• Sudden onset of chest pain

• Localized chest pain with coughing

Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of these signs.

Preventing Infection

The most common causes of infection following total knee replacement surgery are from bacteria that enter the bloodstream during dental procedures, urinary tract infections, or skin infections. These bacteria can lodge around your knee replacement and cause an infection.

For the first two years after your knee replacement, you must take preventive antibiotics before dental or surgical procedures that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. After two years, talk to your orthopaedist and your dentist or urologist to see if you still need preventive antibiotics before any scheduled procedures.

Warning signs of a possible knee replacement infection are:

• Persistent fever (higher than 100 degrees orally)

• Shaking chills

• Increasing redness, tenderness or swelling of the knee wound

• Drainage from the knee wound

• Increasing knee pain with both activity and rest

Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of these signs.

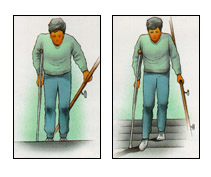

Avoiding Falls

A fall during the first few weeks after surgery can damage your new knee and may result in a need for further surgery. Stairs are a particular hazard until your knee is strong and mobile. You should use a cane, crutches, a walker, hand rails or someone to help you until you have improved your balance, flexibility and strength.

Your surgeon and physical therapist will help you decide what assistive aides will be required following surgery and when those aides can safely be discontinued.

How Your New Knee Is Different

You may feel some numbness in the skin around your incision. You also may feel some stiffness, particularly with excessive bending activities. Improvement of knee motion is a goal of total knee replacement, but restoration of full motion is uncommon. The motion of your knee replacement after surgery is predicted by the motion of your knee prior to surgery. Most patients can expect to nearly fully straighten the replaced knee and to bend the knee sufficiently to go up and down stairs and get in and out of a car. Kneeling is usually uncomfortable, but it is not harmful. Occasionally, you may feel some soft clicking of the metal and plastic with knee bending or walking. These differences often diminish with time and most patients find these are minor, compared to the pain and limited function they experienced prior to surgery.

Your new knee may activate metal detectors required for security in airports and some buildings. Tell the security agent about your knee replacement if the alarm is activated.

After surgery, make sure you also do the following:

• Participate in regular light exercise programs to maintain proper strength and mobility of your new knee.

• Take special precautions to avoid falls and injuries. Individuals who have undergone total knee replacement surgery and suffer a fracture may require more surgery.

• Notify your dentist that you had a knee replacement. You should be given antibiotics before all dental surgery for the rest of your life.

• See your orthopaedic surgeon periodically for a routine follow-up examination and X-rays, usually once a year.

Your orthopaedic surgeon is a medical doctor with extensive training in the diagnosis and nonsurgical and surgical treatment of the musculoskeletal system, including bones, joints, ligaments, tendons, muscles and nerves.

Unicompartmental Arthroplasty and Tibial Osteotomy

Osteotomy and Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Total joint replacement (arthroplasty) is a common and very successful surgery for people with degenerative arthritis (osteoarthritis) of the knee. Two other surgeries can also restore knee function and significantly diminish osteoarthritis pain in carefully selected patients. If osteoarthritis damage to your knee meets certain qualifications, a doctor may recommend either osteotomy or unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA).

Osteoarthritis damage to the knee

A normal knee glides smoothly because articular cartilage covers the ends of the bones that form joints. Osteoarthritis damages the cartilage, progressively wearing it away. The ends of the bones become rough like pieces of sandpaper. Damaged cartilage can cause the joint to "stick" or lock when you use it. Your knee may get painful, stiff and lose range of motion. See your doctor to diagnose osteoarthritis.

Provide your complete medical history including detailed descriptions of osteoarthritis symptoms and when they began. Have you tried nonsurgical treatments such as rest, weight loss and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication for pain? Does it hurt too much to get dressed, bathe or walk up stairs? The doctor will check your knee's range of motion, ligament stability and angular deformity. He or she will observe your knees while you stand and walk, and examine your hips, feet and ankles. Both knees will probably be X-rayed.

Your doctor's recommendation of a surgical procedure for osteoarthritis knee repair depends in part upon how it is damaged. The knee has three joints (compartments), any or all of which can be impacted by osteoarthritis:

• The inside (medial) compartment (medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle) is most commonly involved, producing a bowleg (genu varum) deformity.

• The outside (lateral) compartment (lateral tibial plateau and lateral femoral condyle) is sometimes involved in women or obese people, producing a knock-knee (genu valgum) deformity.

• The kneecap (patellofemoral) compartment (patella and femoral trochlear notch) may also develop osteoarthritis.

If you have early stage arthritis confined to one part of the knee, your doctor may recommend osteotomy or UKA.

Osteotomy

Osteotomy may be appropriate if you are younger than age 60, active or overweight. There must also be uneven damage to the joint, correctable deformity and no inflammation. The surgeon reshapes the shinbone (tibia) or thighbone (femur) to improve your knee's alignment. The healthy bone and cartilage is realigned to compensate for the damaged tissue. Knee osteotomy surgically repositions the joint, realigning the mechanical axis of the limb away from the diseased area. This lets your knee glide freely and carry weight evenly on a more normal compartment.

• Proximal tibial valgus osteotomy treats arthritis of the medial compartment, correcting a knee that angles inward (varus deformity).

• Distal femoral varus osteotomy treats arthritis of the lateral compartment, correcting a knee that angles outward (valgus deformity).

The doctor may use one of several techniques to hold the joint in place (i.e., immobilization with a cast, staples or internal plate devices).

Outcome: Osteotomy relieves pain and may delay the progression of osteoarthritis. Cosmetically, the knee may not look symmetrical after osteotomy. There's a chance you will eventually need TKA, which can be a more technically challenging procedure after you've had an osteotomy. Infections and other complications are possible. Depending upon how quickly you heal, you will need to walk with crutches for 1-3 months. After that you begin rehabilitative leg strengthening and walking exercises. You may be able to resume your full activities after 3-6 months.

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) may be appropriate if you are age 60 or older, not obese and relatively sedentary. Among other specific qualifications, your knee must have:

• An intact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

• No significant inflammation.

• No damage to the other compartments, calcification of cartilage or dislocation.

Your doctor will verify that your knee meets the requirements when he or she begins the surgery. (Note: If your knee does not meet the qualifications, you may need TKA.) The surgeon removes diseased bone and puts an implant (prosthesis) in its place. The two small replacement parts are secured to the rest of your knee. You can get UKA surgery on both knees at the same time if you need it.

Outcome: UKA aleviates pain and may delay the need for TKA. You get better joint motion and function because the procedure preserves both cruciate ligaments and other healthy parts of the knee. You also keep the bone stock in the kneecap joint and the other compartment, which can be helpful if you ever need conversion to TKA in the future. Complications are rare, but the new joint could develop an infection or slip out of place after surgery. For these reasons, your doctor may want to see you for follow-up visits after surgery. You will have to do range of motion and other physical therapy exercises to rehabilitate your knee. Recovery from UKA is faster than from TKA or osteotomy.

Although UKA was a controversial procedure when it was first introduced about 30 years ago, success rates have improved thanks to precise patient selection, refined surgical techniques and improved implant design. UKA has a higher initial success rate and fewer complications compared with osteotomy. Other advantages include less blood loss during surgery and cheaper cost.

Arthroscopic Meniscectomy

Knee Arthroscopy

If you have persistent pain, catching, or swelling in your knee, a procedure known as arthroscopy may help relieve these problems.

Arthroscopy allows an orthopaedic surgeon to diagnose and treat knee disorders by providing a clear view of the inside of the knee with small incisions, utilizing a pencil-sized instrument called an arthroscope. The scope contains optic fibers that transmit an image of your knee through a small camera to a television monitor. The TV image allows the surgeon to thoroughly examine the interior of your knee and determine the source of your problem. During the procedure, the surgeon also can insert surgical instruments through other small incisions in your knee to remove or repair damaged tissues.

Modern or contemporary arthroscopy of the knee was first performed in the late 1960s. With improvements of arthroscopes and higher-resolution cameras, the procedure has become highly effective for both the accurate diagnosis and proper treatment of knee problems. Today, arthroscopy is one of the most common orthopaedic procedures in the United States.

Whether you have just begun exploring treatment options for your problem knee or have already decided, with your orthopaedic surgeon, to have an arthroscopy, this booklet will help you understand more about this valuable procedure.

How the Normal Knee Works

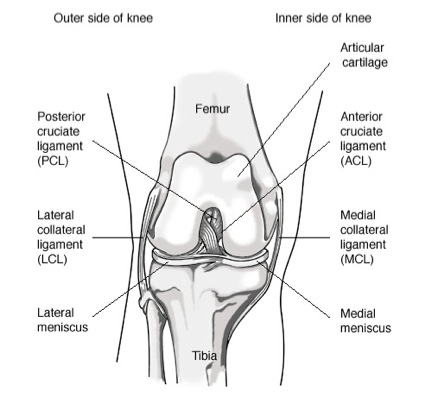

The knee is the largest joint in the body, and one of the most easily injured. It is made up of the lower end of the thigh bone (femur), the upper end of the shin bone (tibia), and the knee cap (patella), which slides in a groove on the end of the femur. Four bands of tissue, the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, and the medial and lateral collateral ligaments connect the femur and the tibia and provide joint stability. Strong thigh muscles give the knee strength and mobility.

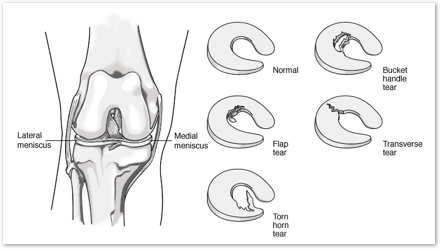

The surfaces where the femur, tibia and patella touch are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth substance that cushions the bones and enables them to glide freely. Semicircular rings of tough fibrous-cartilage tissue called the lateral and medial menisci act as shock absorbers and stabilizers.

The bones of the knee are surrounded by a thin, smooth tissue capsule lined by a thin synovial membrane which releases a special fluid that lubricates the knee, reducing friction to nearly zero in a healthy knee.

Knee Problems

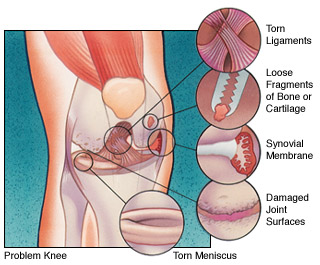

Normally, all parts of the knee work together in harmony. But sports, work injuries, arthritis, or weakening of the tissues with age can cause wear and inflammation, resulting in pain and diminished knee function.

Arthroscopy can be used to diagnose and treat many of these problems:

• Loose fragments of bone or cartilage.

• Damaged joint surfaces or softening of the articular cartilage known as chondromalacia.

• Inflammation of the synovial membrane, such as rheumatoid or gouty arthritis.

• Abnormal alignment or instability of the kneecap.

• Torn ligaments including the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.

By providing a clear picture of the knee, arthroscopy can also help the orthopaedic surgeon decide whether other types of reconstructive surgery would be beneficial.

Is Arthroscopy for You?

Your family physician can refer you to an orthopaedic surgeon for an evaluation to determine whether you could benefit from arthroscopy.

Signs that you may be a candidate for this procedure include swelling, persistent pain, catching, giving-way, and loss of confidence in your knee. When other treatments such as the regular use of medications, knee supports, and physical therapy have provided minimal or no improvement, you may benefit from arthroscopy.

Most arthroscopies are performed on patients between the ages of 20 and 60, but patients younger than 10 years and older than 80 years have benefited from the procedure.

The Orthopaedic Knee Evaluation

The orthopaedic knee evaluation consists of three components:

• A medical history, in which your orthopaedic surgeon gathers information about your general health and asks you about your symptoms.

• A physical examination to assess your knee motion and stability, muscle strength and overall leg alignment.

• X-rays to evaluate the bones of your knee. Your orthopaedic surgeon may also arrange for you to have an MRI to provide more information about the soft tissues of your knee. An MRI uses magnetic sound waves to create images. They are not X-rays. Blood tests may be obtained to determine if you have arthritis.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will review the results of your evaluation with you and discuss whether arthroscopy would be the best method to further diagnose and treat your knee problem. Other treatment options, such as medications or other surgical procedures also will be discussed and considered.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will explain the potential risks and complications of knee arthroscopy, including those related to the surgery itself and those that can occur after your surgery.

Preparing for Surgery

If you decide to have arthroscopy, you may be asked to have a complete physical with your family physician before surgery to assess your health and to rule out any conditions that could interfere with your surgery.

Before surgery, tell your orthopaedic surgeon about any medications that you are taking. You will be informed which medications you should stop taking before surgery.

Tests, such as blood samples or a cardiogram, may be ordered by your orthopaedic surgeon to help plan your procedure.

Your Arthroscopic Knee Surgery

Almost all arthroscopic knee surgery is done on an outpatient basis. Your hospital or surgery center will contact you about the specific details for your surgery, but usually you will be asked to arrive at the hospital an hour or two prior to your surgery. Do not eat or drink anything after midnight the night before your surgery.

After arrival, you will be evaluated by a member of the anesthesia team. Arthroscopy can be performed under local, regional, or general anesthesia. Local anesthesia numbs your knee, regional anesthesia numbs you below your waist, and general anesthesia puts you to sleep. The anesthesiologist will help you determine which would be the best for you.

If you have local or regional anesthesia, you may be able to watch the procedure on a TV screen, if you wish.

The orthopaedic surgeon will make a few small incisions in your knee. A sterile solution will be used to fill the knee joint and rinse away any cloudy fluid, providing a clear view of your knee.

The surgeon will then insert the arthroscope to properly diagnose your problem, using the TV image to guide the arthroscope. If surgical treatment is needed, the surgeon can use a variety of small surgical instruments (e.g., scissors, clamps, motorized shavers, or lasers) through another small incision. This part of the procedure usually lasts 45 minutes to 1 1/2 hours.

Common treatments with knee arthroscopy include:

• Removal or repair of torn meniscal cartilage.

• Reconstruction of a torn cruciate ligament.

• Trimming of torn pieces of articular cartilage.

• Removal of loose fragments of bone or cartilage.

• Removal of inflamed synovial tissue.

At the conclusion of your surgery, the surgeon may close your incisions with a suture or paper tape and cover them with a bandage.

You will be moved to the recovery room. Usually, you will be ready to go home in one or two hours. You should have someone with you to drive you home.

Your Recovery at Home

Recovery from knee arthroscopy is much faster than recovery from traditional open knee surgery. Still, it is important to follow your orthopaedic surgeon's instructions carefully after you return home. You should ask someone to check on you that evening.

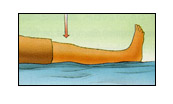

Swelling Keep your leg elevated as much as possible for the first few days after surgery. Apply ice as recommended by your orthopaedic surgeon to relieve swelling and pain.

Dressing Care: You will leave the hospital with a dressing covering your knee. You may remove the dressing the day after surgery. You may shower, but should avoid directing water at the incisions. Do not soak in a tub. Keep your incisions clean and dry.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will see you in the office a few days after surgery to check your progress, review the surgical findings, and begin your postoperative treatment program.

Bearing Weight: After most arthroscopic surgeries, you can walk unassisted but your orthopaedic surgeon may advise you to use crutches, a cane, or a walker for a period of time after surgery. You can gradually put more weight on your leg as your discomfort subsides and you regain strength in your knee. Your surgeon may allow you to drive after a week.

Exercises to Strengthen Your Knee: you should exercise your knee regularly for several weeks following surgery to strengthen the muscles ofyour leg and knee. A physical therapist may help you with your exercise program if your orthopaedic surgeon recommends specific exercises.

Medications: your orthopaedic surgeon may prescribe antibiotics to help prevent an infection and pain medication to help relieve discomfort following your surgery.

Complications: potential postoperative problems with knee arthroscopy include infection, blood clots, and an accumulation of blood in the knee. These occur infrequently and are minor and treatable.

Warning Signs

Call your orthopaedic surgeon immediately if you experience any of the following:

• Fever.

• Chills.

• Persistent warmth or redness around the knee.

• Persistent or increased pain.

• Significant swelling in your knee.

• Increasing pain in your calf muscle.

• Shortness of breath or chest pain.

Reasonable Expectations After Arthroscopic Surgery

Although arthroscopy can be used to treat many problems, you may have some activity limitations even after recovery. The outcome of your surgery will often be determined by the degree of injury or damage found in your knee. For example, if you damage your knee from jogging and the smooth articular cushion of the weight-bearing portion of the knee has worn away completely, then full recovery may not be possible. You may be advised to find a low-impact alternative form of exercise. An intercollegiate or professional athlete often sustains the same injury as a weekend recreational athlete, but the potential for recovery may be improved by the over-development of knee muscles. Physical exercise and rehabilitation will play an important role in your final outcome. A formal physical therapy program also may add something to your final result.

A return to intense physical activity should only be done under the direction of your surgeon.

It is reasonable to expect that by six to eight weeks you should be able to engage in most of your former physical activities as long as they do not involve significant weight-bearing impact. Twisting maneuvers may have to be avoided for a longer time.

If your job involves heavy work, such as a construction laborer, you may require more time to return to your job than if you have a sedentary job.

Your orthopaedic surgeon is a medical doctor with extensive training in the diagnosis and nonsurgical and surgical treatment of the musculoskeletal system, including bones, joints, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and nerves.

ACL reconstruction / PCL reconstruction

Price

Knee Ligament Injuries

In 2003 more than 9.5 million people visited orthopaedic surgeons because of knee problems. (Source: National Center for Health Statistics; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.) The knee is the largest joint in the body and is vital to movement. Two sets of ligaments in the knee give it stability: the cruciate and the collateral ligaments.

Cruciate ligaments

The cruciate ligaments are located inside the knee joint and connect the thighbone (femur) to the shinbone (tibia). They are made of many strands and function like short ropes that hold the knee joint tightly in place when the leg is bent or straight. This stability is needed for proper knee joint movement.

The name, cruciate, derives from the word crux, meaning cross, and crucial. The cruciate ligaments not only lie inside the knee joint, they crisscross each other to form an "x". The cruciate ligament located toward the front of the knee is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and the one located toward the rear of the knee is called the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).

ACL injuries

The ACL prevents the shinbone from sliding forwards beneath the thighbone. The ACL can be injured in several ways:

• Changing direction rapidly

• Slowing down when running

• Landing from a jump

• Direct contact, such as in a football tackle

Recognizing an ACL injury

If you injure your ACL, you may not feel any pain immediately. However, you might hear a popping noise and feel your knee give out from under you. Within 2 to 12 hours, the knee will swell, and you will feel pain when you try to stand. Apply ice to control swelling and elevate your knee until you can see an orthopaedic surgeon.

If you walk or run on an injured ACL, you can damage the cushioning cartilage in the knee. For example, you may plant the foot and turn the body to pivot, only to have the shinbone stay in place as the thighbone above it moves with the body.

Diagnosing an ACL injury

A diagnosis of ACL injury is based on a thorough physical examination of the knee. The exam may include several tests to see if the knee stays in the proper position when pressure is applied from different directions. Your orthopaedist may order an X-ray and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or, in some cases, arthroscopic inspection.

A partial tear of the ACL may or may not require surgical treatment. A complete tear is more serious. Complete tears, especially in younger athletes, may require reconstruction.

Treating ACL tears

Both nonoperative and operative treatment choices are available.

Nonoperative treatment:

• May be used because of a patient's age or overall low activity level.

• May be recommended if the overall stability of the knee seems good.

• Involves a treatment program of muscle strengthening, often with the use of a brace to provide stability.

• Operative treatment (either arthroscopic or open surgery): Uses a strip of tendon, usually taken from the patient's knee (patellar tendon) or hamstring muscle, that is passed through the inside of the joint and secured to the thighbone and shinbone.

• Is followed by an exercise and rehabilitation program to strengthen the muscles and restore full joint mobility.

PCL injuries

The posterior cruciate ligament, or PCL, is not injured as frequently as the ACL. PCL sprains usually occur because the ligament was pulled or stretched too far, a blow to the front of the knee, or a simple misstep.

PCL injuries disrupt knee joint stability because the shinbone can sag backwards. The ends of the thighbone and shinbone rub directly against each other, causing wear and tear to the thin, smooth articular cartilage. This abrasion may lead to arthritis in the knee.

Treating PCL injuries

Patients with PCL tears often do not have symptoms of instability in their knees, so surgery is not always needed. Many athletes return to activity without significant impairment after completing a prescribed rehabilitation program.

However, if the PCL injury pulls a piece of bone out of the top of the shinbone, surgery is needed to reattach the ligament. Knee function after this surgery is often quite good.

Collateral ligaments

The collateral ligaments are located at the inner side and outer side of the knee joint. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) connects the thighbone to the shinbone and provides stability to the inner side of the knee. The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) connects the thighbone to the other bone in the lower portion of your leg (fibula) and stabilizes the outer side.

Injuries to the MCL are usually caused by contact on the outside of the knee and are accompanied by sharp pain on the inside of the knee. The LCL is rarely injured.

Collateral ligament injuries

If the medial collateral ligament (MCL) has a small partial tear, conservative treatment usually works. Remember the acronym RICE: Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation.

Rest the knee to give the ligament time to heal. Ice can be applied two or three times a day for 15 to 20 minutes each time.

Compress the injury to limit swelling. You may have to wear a bandage or brace for a while.

Elevate the knee whenever possible.

You should also consult your physician about a course of rehabilitation exercises for good healing.

If the collateral ligament is completely torn or torn in such a way that ligament fibers cannot heal, you may need surgery. Repair may bring good results, with a return to good knee stability. After satisfactory rehabilitation, many people resume their previous levels of activity.

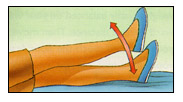

A rehabilitation plan is needed if you have a cruciate or collateral ligament injury. Most rehabilitation plans include:

• Passive range-of-motion exercises designed to restore flexibility.

• Braces to control joint movement.

• Exercises to strengthen the quadriceps muscles in the front of the thigh. (Muscle strength is needed to provide the knee joint with as much support and stability as possible when weight is placed on it.)

• Additional exercises on a high-seat exercise bicycle, followed by more strenuous quadriceps exercise.

Your progress and the ability of the knee to function as a normal knee will determine how long you must use crutches and a brace.

Minimally Invasive Total Hip Replacement

Whether you have just begun exploring treatment options or have already decided with your orthopaedic surgeon to undergo hip replacement surgery, this information will help you understand the benefits and limitations of this orthopaedic treatment. You'll learn how a normal hip works and the causes of hip pain, what to expect from hip replacement surgery and what exercises and activities will help restore your mobility and strength and enable you to return to everyday activities.

If your hip has been damaged by arthritis, a fracture or other conditions, common activities such as walking or getting in and out of a chair may be painful and difficult. Your hip may be stiff and it may be hard to put on your shoes and socks. You may even feel uncomfortable while resting.

If medications, changes in your everyday activities, and the use of walking aids such as a cane are not helpful, you may want to consider hip replacement surgery. By replacing your diseased hip joint with an artificial joint, hip replacement surgery can relieve your pain, increase motion, and help you get back to enjoying normal, everyday activities.

First performed in 1960, hip replacement surgery is one of the most important surgical advances of the last century. Since then, improvements in joint replacement surgical techniques and technology have greatly increased the effectiveness of this surgery. Today, more than 193,000 total hip replacements are performed each year in the United States. Similar surgical procedures are performed on other joints, including the knee, shoulder, and elbow.

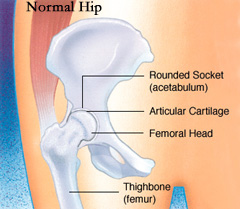

How the normal hip works

The hip is one of your body's largest weight-bearing joints. It consists of two main parts: a ball (femoral head) at the top of your thighbone (femur) that fits into a rounded socket (acetabulum) in your pelvis. Bands of tissue called ligaments (hip capsule) connect the ball to the socket and provide stability to the joint.

The bone surfaces of your ball and socket have a smooth durable cover of articular cartilage that cushions the ends of the bones and enables them to move easily.

A thin, smooth tissue called synovial membrane covers all remaining surfaces of the hip joint. In a healthy hip, this membrane makes a small amount of fluid that lubricates and almost eliminates friction in your hip joint.

Normally, all of these parts of your hip work in harmony, allowing you to move easily and without pain.

Common causes of hip pain and loss of hip mobility

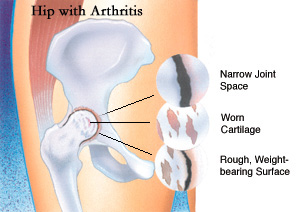

The most common cause of chronic hip pain and disability is arthritis. Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and traumatic arthritis are the most common forms of this disease.

Osteoarthritis usually occurs after age 50 and often in an individual with a family history of arthritis. It may be caused or accelerated by subtle irregularities in how the hip developed. In this form of the disease, the articular cartilage cushioning the bones of the hip wears away. The bones then rub against each other, causing hip pain and stiffness.

Rheumatoid Arthritis is an autoimmune disease in which the synovial membrane becomes inflamed, produces too much synovial fluid, and damages the articular cartilage, leading to pain and stiffness.

Traumatic Arthritis can follow a serious hip injury or fracture. A hip fracture can cause a condition known as avascular necrosis. The articular cartilage becomes damaged and, over time, causes hip pain and stiffness.

Is hip replacement surgery for you?

The decision whether to have hip replacement surgery should be a cooperative one between you, your family, your primary care doctor, and your orthopaedic surgeon. The process of making this decision typically begins with a referral by your doctor to an orthopaedic surgeon for an initial evaluation.

Although many patients who undergo hip replacement surgery are age 60 to 80, orthopaedic surgeons evaluate patients individually. Recommendations for surgery are based on the extent of your pain, disability and general health status, not solely on age.

You may benefit from hip replacement surgery if:

• Hip pain limits your everyday activities such as walking or bending.

• Hip pain continues while resting, either day or night.

• Stiffness in a hip limits your ability to move or lift your leg.

• You have little pain relief from anti-inflammatory drugs or glucosamine sulfate.

• You have harmful or unpleasant side effects from your hip medications.

• Other treatments such as physical therapy or the use of a gait aid such as a cane don't relieve hip pain.

The orthopaedic evaluation

Your orthopaedic surgeon will review the results of your evaluation with you and discuss whether hip replacement surgery is the best method to relieve your pain and improve your mobility. Other treatment options such as medications, physical therapy or other types of surgery also may be considered.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will explain the potential risks and complications of hip replacement surgery, including those related to the surgery itself and those that can occur over time after your surgery. These risks and complications are discussed later in this booklet.

• A medical history, in which your orthopaedic surgeon gathers information about your general health and asks questions about the extent of your hip pain and how it affects your ability to perform every day activities.

• A physical examination to assess your hip's mobility, strength and alignment.

• X-rays to determine the extent of damage or deformity in your hip.

• Occasionally, blood tests or other tests such as an Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or a bone scan may be needed to determine the condition of the bone and soft tissues of your hip.

What to expect from hip replacement surgery

An important factor in deciding whether to have hip replacement surgery is understanding what the procedure can and can't do.

Most people who undergo hip replacement surgery experience a dramatic reduction of hip pain and a significant improvement in their ability to perform the common activities of daily living. However, hip replacement surgery will not enable you to do more than you could before your hip problem developed.

Following surgery, you will be advised to avoid certain activities, including jogging and high-impact sports, for the rest of your life. You may be asked to avoid specific positions of the joint that could lead to dislocation.

Even with normal use and activities, an artificial joint (prosthesis) develops some wear over time. If you participate in high-impact activities or are overweight, this wear may accelerate and cause the prosthesis to loosen and become painful.

Preparing for surgery

Medical Evaluation. If you decide to have hip replacement surgery, you may be asked to have a complete physical by your primary care doctor before your surgery. This is needed to assess your health and find conditions that could interfere with your surgery or recovery.

Tests. Several tests such as blood samples, a cardiogram, chest X-rays and urine samples may be needed to help plan your surgery.

Preparing Your Skin. Your skin should not have any infections or irritations before surgery. If either is present, contact your orthopaedic surgeon for a program to improve your skin before your surgery.

Blood Donations. You may be advised to donate your own blood prior to surgery. It will be stored in case you need blood after surgery.

Medications. Tell your orthopaedic surgeon about the medications you are taking. Your orthopaedist or your primary care doctor will advise you which medications you should stop or can continue taking before surgery.

Weight Loss. If you are overweight, your doctor may ask you to lose some weight before surgery to minimize the stress on your new hip, and possibly decrease the risks of surgery

Dental Evaluation. Although infections after hip replacement are not common, an infection can occur if bacteria enter your bloodstream. Because bacteria can enter the bloodstream during dental procedures, you should consider getting treatment for significant dental diseases (including tooth extractions and periodontal work) before your hip replacement surgery. Routine cleaning of your teeth should be delayed for several weeks after surgery.

Urinary Evaluation. Individuals with a history of recent or frequent urinary infections and older men with prostate disease should consider a urological evaluation before surgery.

Social Planning. Although you will be able to walk with crutches or a walker soon after surgery, you will need some help for several weeks with such tasks as cooking, shopping, bathing and laundry. If you live alone, your surgeon's office, a social worker, or a discharge planner at the hospital can help you make advance arrangements to have someone assist you at your home. A short stay in an extended care facility during your recovery after surgery also may be arranged.

Home planning

Here are some items and home modifications that will make your return home easier during your recovery.

• Securely fastened safety bars or handrails in your shower or bath

• Secure handrails along all stairways

• A stable chair for your early recovery with a firm seat cushion that allows your knees to remain lower than your hips, a firm back and two arms

• A raised toilet seat

• A stable shower bench or chair for bathing

• A long-handled sponge and shower hose

• A dressing stick, a sock aid and a long-handled shoe horn for putting on and taking off shoes and socks without excessively bending your new hip

• A reacher that will allow you to grab objects without excessive bending of your hips

• Firm pillows to sit on that keep your knees lower than your hips for your chairs, sofas and car

• Removal of all loose carpets and electrical cords from the areas where you walk in your home

Your surgery

You will most likely be admitted to the hospital on the day of your surgery. Prior to admission, a member of the anesthesia team will evaluate you. The most common types of anesthesia for hip replacement surgery are general anesthesia (which puts you to sleep throughout the procedure and uses a machine to help you breath) or spinal anesthesia (which allows you to breath on your own but anesthetizes your body from the waist down). The anesthesia team will discuss these choices with you and help you decide which type of anesthesia is best for you.

Surgical procedure

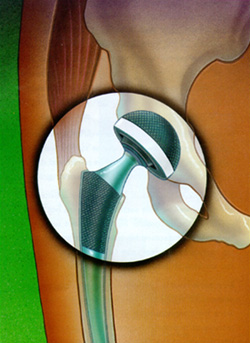

The surgical procedure takes a few hours. Your orthopaedic surgeon will remove the damaged cartilage and bone, then position new metal, plastic or ceramic joint surfaces to restore the alignment and function of your hip.

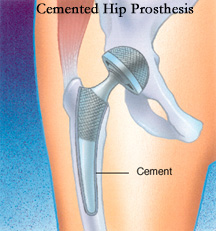

Many different types of designs and materials are currently used in artificial hip joints. All of them consist of two basic components: the ball component (made of a highly polished strong metal or ceramic material) and the socket component (a durable cup of plastic, ceramic or metal, which may have an outer metal shell).

Special surgical cement may be used to fill the gap between the prosthesis and remaining natural bone to secure the artificial joint.

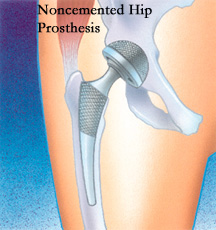

A noncemented prosthesis has also been developed which is used most often in younger, more active patients with strong bone. The prosthesis may be coated with textured metal or a special bone-like substance, which allows bone to grow into the prosthesis.

A combination of a cemented ball and a noncemented socket may be used.

Your orthopaedic surgeon will choose the type of prosthesis that best meets your needs.

After surgery, you will be moved to the recovery room where you will remain for one to two hours while your recovery from anesthesia is monitored. After you awaken fully, you will be taken to your hospital room.

A special note about minimally invasive total hip replacement

Over the past several years, orthopaedic surgeons have been developing new techniques, known as minimally invasive hip replacement surgery, for inserting total hip replacements through smaller incisions. It is hoped, but not yet proven, that this may allow for quicker, less painful recovery and more rapid return to normal activities. Minimally invasive and small incision total hip replacement surgery is a rapidly evolving area. While certain techniques have proven to be safe, others may be associated with an increased risk of complications such as nerve and artery injuries, wound healing problems, infection, fracture of the femur and malposition of the implants, which can contribute to premature wear, dislocation and loosening of your hip replacement. Patients who have marked deformity of the joint, those who are heavy or muscular, and those who have other health problems, which can contribute to wound healing problems, appear to be at higher risk of problems. Your orthopaedic surgeon can talk to you about his or her experience with minimally invasive hip replacement surgery and the possible risks and benefits of minimally invasive hip replacement surgery. The AAOS and the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons have developed information for patients about minimally invasive hip replacement surgery.

Your stay in the hospital

You will usually stay in the hospital for a few days. After surgery, you will feel pain in your hip. Pain medication will be given to make you as comfortable as possible.

To avoid lung congestion after surgery, you will be asked to breathe deeply and cough frequently.

To protect your hip during early recovery, a positioning splint, such as a V-shaped pillow placed between your legs, may be used.

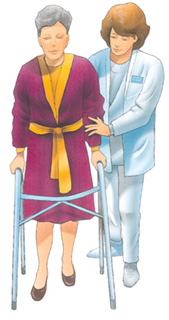

Walking and light activity are important to your recovery and will begin the day of or the day after your surgery. Most hip replacement patients begin standing and walking with the help of a walking support and a physical therapist the day after surgery. The physical therapist will teach you specific exercises to strengthen your hip and restore movement for walking and other normal daily activities.

Possible complications after surgery

The complication rate following hip replacement surgery is low. Serious complications, such as joint infection, occur in less than 2 percent of patients. Major medical complications, such as heart attack or stroke, occur even less frequently. However, chronic illnesses may increase the potential for complications. Although uncommon, when these complications occur they can prolong or limit your full recovery.

Blood clots in the leg veins or pelvis are the most common complication of hip replacement surgery. Your orthopaedic surgeon may prescribe one or more measures to prevent blood clots from forming in your leg veins or becoming symptomatic. These measure may include special support hose, inflatable leg coverings, ankle pump exercises and blood thinners.

Leg-length inequality may occur or may become or seem worse after hip replacement. Your orthopaedic surgeon will take this into account, in addition to other issues, including the stability and biomechanics of the hip. Some patients may feel more comfortable with a shoe lift after surgery.

Other complications such as dislocation, nerve and blood vessel injury, bleeding, fracture and stiffness can occur. In a small number of patients, some pain can continue, or new pain can occur after surgery.

Over years, the hip prosthesis may wear out or loosen. This problem will likely be less common with newer materials and techniques. When the prosthesis wears, bone loss may occur because of the small particles produced at the wearing surface. This process is called osteolysis.

Your recovery at home

The success of your surgery will depend in large measure on how well you follow your orthopaedic surgeon's instructions regarding home care during the first few weeks after surgery

Wound Care. You will have stitches or staples running along your wound or a suture beneath your skin. The stitches or staples will be removed about two weeks after surgery.

Avoid getting the wound wet until it has thoroughly sealed and dried. A bandage may be placed over the wound to prevent irritation from clothing or support stockings.

Diet. Some loss of appetite is common for several weeks after surgery. A balanced diet, often with an iron supplement, is important to promote proper tissue healing and restore muscle strength. Be sure to drink plenty of fluids.

Activity. Exercise is a critical component of home care, particularly during the first few weeks after surgery. You should be able to resume most normal light activities of daily living within three to six weeks following surgery. Some discomfort with activity and at night is common for several weeks.

Your activity program should include:

• A graduated walking program, initially in your home and later outside

• Walking program to slowly increase your mobility and endurance

• Resuming other normal household activities

• Resuming sitting, standing, walking up and down stairs

• Specific exercises several times a day to restore movement

• Specific exercises several times a day to strength your hip joint

• May wish to have a physical therapist help you at home

Avoiding problems after surgery

Blood Clot Prevention. Follow your orthopaedic surgeon's instructions carefully to minimize the potential risk of blood clots, which can occur during the first several weeks of your recovery.

Warning signs of possible blood clots include:

• Pain in your calf and leg, unrelated to your incision

• Tenderness or redness of your calf

• Swelling of your thigh, calf, ankle or foot

Warning signs that a blood clot has traveled to your lung include:

• Shortness of breath

• Chest pain, particularly with breathing

Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of these signs.

Preventing infection

The most common causes of infection following hip replacement surgery are from bacteria that enter the bloodstream during dental procedures, urinary tract infections, or skin infections. These bacteria can lodge around your prosthesis.

Following your surgery, you may need to take antibiotics prior to dental work, including dental cleanings, or any surgical procedure that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. For many patients with a normal immune system the AAOS and ADA recommend dental prophylaxis for two years after a primary total joint surgery. A complete discussion of this topic is available on the AAOS patient education Web site, Your Orthopaedic Connection.

Warning signs of a possible hip replacement infection are:

• Persistent fever (higher than 100 degrees orally)

• Shaking chills

• Increasing redness, tenderness or swelling of the hip wound

• Drainage from the hip wound

• Increasing hip pain with both activity and rest

Notify your doctor immediately if you develop any of these signs.

Avoiding falls

A fall during the first few weeks after surgery can damage your new hip and may result in a need for more surgery. Stairs are a particular hazard until your hip is strong and mobile. You should use a cane, crutches, a walker or handrails, or have someone help you until you improve your balance, flexibility and strength.

Your surgeon and physical therapist will help you decide what assistive aides will be required following surgery, and when those aides can safely be discontinued.

Other precautions